Table of Contents

Risk adjustment is a cornerstone of managing cost, quality, and performance in modern healthcare financing. In Medicare Advantage and value-based care models, effective risk adjustment ensures organizations are fairly compensated for the health risk of their patient populations. For healthcare executives – from VPs of Care Management and Risk Adjustment to Chief Medical Officers and CEOs – understanding risk adjustment is critical to financial sustainability and high-quality care delivery.

What Is Risk Adjustment?

Risk adjustment is a method of adjusting payments or comparisons to reflect the underlying health status and risk profile of patients. In simple terms, it estimates the expected cost of caring for a patient based on their diagnoses and demographics. Sicker patients with multiple chronic conditions are assigned higher risk scores (also known as Risk Adjustment Factor or RAF scores) to predict higher costs, while healthier patients get lower scores.

A risk score is a numeric value representing a patient’s predicted cost relative to the average Medicare beneficiary (which is defined as 1.0). For example, a RAF score of 1.0 corresponds to average expected cost, 2.0 would be roughly double the average, and 0.5 would be half the average.

By “evening the playing field,” risk adjustment helps ensure healthcare providers and plans are paid fairly for the patients they serve. Without it, organizations might avoid high-risk patients because of higher costs. Risk adjustment enables risk stratification – categorizing patient populations by risk level – so that plans and providers can allocate resources and manage care for high-risk groups appropriately. In practice, this means using data from medical claims and diagnoses to assign each member a risk score, which is then used to adjust payments or to benchmark performance.

Why Risk Adjustment Matters in Medicare Advantage

Medicare Advantage (MA) plans (Medicare Part C) receive capitated per-member-per-month payments to cover Part A and B benefits for each enrollee. Risk adjustment is fundamental in MA because it adjusts these payments based on each enrollee’s health status and expected costs. In effect, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) pays more for a beneficiary with serious chronic illnesses and less for a relatively healthy beneficiary. This ensures MA plans have predictable, actuarially sound payments and adequate resources to care for patients with complex conditions.

Originally implemented in the late 1990s, risk adjustment was designed to provide sufficient financing to plans that enroll higher-risk beneficiaries and to prevent cherry-picking (i.e. plans selecting only healthy members). In the absence of risk adjustment, a plan that enrolls sicker-than-average patients would incur higher costs without higher revenue, which could discourage plans from serving those patients.

Today, risk adjustment in MA means even high-risk seniors have access to coverage, since plans are compensated for taking on their care. It levels the playing field among MA organizations and stabilizes plan finances: revenue aligns with the health risk of the enrolled population, allowing executive teams to invest in care management programs for chronic conditions knowing the funding will be there to support those high-need members.

For MA executives, risk adjustment directly impacts the bottom line. RAF scores drive revenue – under-coding (failing to capture all diagnosable conditions) can lead to underpayment, while accurate coding ensures the plan receives funds commensurate with members’ health needs. Moreover, risk-adjusted performance metrics allow fair quality comparisons among plans. In sum, effective risk adjustment in Medicare Advantage is essential for balancing financial sustainability with the mission of caring for all beneficiaries, regardless of health status.

How Risk Adjustment Supports Value-Based Care

Value-based care (VBC) models tie payments to quality and outcomes rather than volume, which often means providers and health systems take on financial risk for patient populations. Risk adjustment is a critical tool in these models to ensure fairness and viability. It links payments to the actual clinical complexity of patients, so providers aren’t penalized for serving sicker or higher-need populations.

When healthcare organizations enter value-based contracts – such as Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), bundled payments, or capitated primary care models – they rely on risk adjustment to set budgets and performance targets that reflect their patient population’s acuity. For instance, an ACO’s spending benchmark is typically risk-adjusted: if an ACO has more chronically ill patients than average, the benchmark is higher to account for those needs. This way, cost and quality outcomes can be judged on a fair basis.

As the American Academy of Family Physicians notes, as providers take on downside risk and per-person payments, they benefit from the same protections that risk adjustment historically provided to health plans. The ability to predict the relative needs and costs of care for patients is crucial for success in VBC, and risk adjustment is the essential tool to inform that understanding.

In practical terms, risk adjustment in VBC means that performance metrics and payments account for patient acuity. A provider group managing frail, multi-chronic patients can still succeed in a value-based contract because risk adjustment will calibrate their financial targets to be achievable given their population. This encourages providers to accept and care for high-risk patients instead of avoiding them.

It also allows value-based programs to focus on improving care quality and outcomes (like reducing hospital readmissions or managing diabetes) knowing that comparisons between providers or health plans are apples-to-apples in terms of patient risk. As a result, risk adjustment supports the goals of value-based care by aligning incentives with patient needs and promoting health equity – ensuring providers have the resources to deliver quality care to even the most complex patients.

Common Risk Adjustment Models (e.g., CMS-HCC)

There are several risk adjustment models used in U.S. healthcare, with the CMS-HCC model being one of the most prominent. CMS-HCC stands for Hierarchical Condition Category, which is the risk adjustment methodology CMS uses for Medicare Advantage and certain other programs. Under the CMS-HCC model, each enrollee’s diagnoses (as coded in claims and encounters) are mapped to a set of condition categories.

Each HCC corresponds to a specific health condition or set of related conditions (for example, there are HCCs for diabetes, chronic heart failure, COPD, etc.). The model is “hierarchical” in that if a patient has multiple related conditions, only the most severe condition in that hierarchy is counted, to avoid double-counting. CMS-HCC models also factor in demographic variables like age, sex, Medicaid dual-eligibility, and disability status.

Using these inputs, CMS calculates an individual risk score for each beneficiary using the CMS-HCC formula. The RAF score is the sum of risk weights for the beneficiary’s demographics and HCCs. An average Medicare beneficiary nationwide has a RAF score of about 1.0 (by design) – indicating expected cost about equal to the national average. Patients with numerous or severe conditions will have RAF scores above 1.0 (meaning higher expected costs), while healthier individuals will be below 1.0. Each year, CMS uses the diagnoses from the prior year to determine each MA enrollee’s risk score for the payment year.

For example, if a patient was treated for diabetes and congestive heart failure last year, those diagnoses contribute to a higher risk score (and higher capitation payment) for the plan in the current year. CMS updates the HCC model periodically; for 2024, CMS introduced a revised model (often called V28) that changes how certain diagnoses map to HCCs and even removed some diagnoses from counting towards risk scores. Such updates aim to improve prediction accuracy and keep the model in line with current healthcare cost patterns.

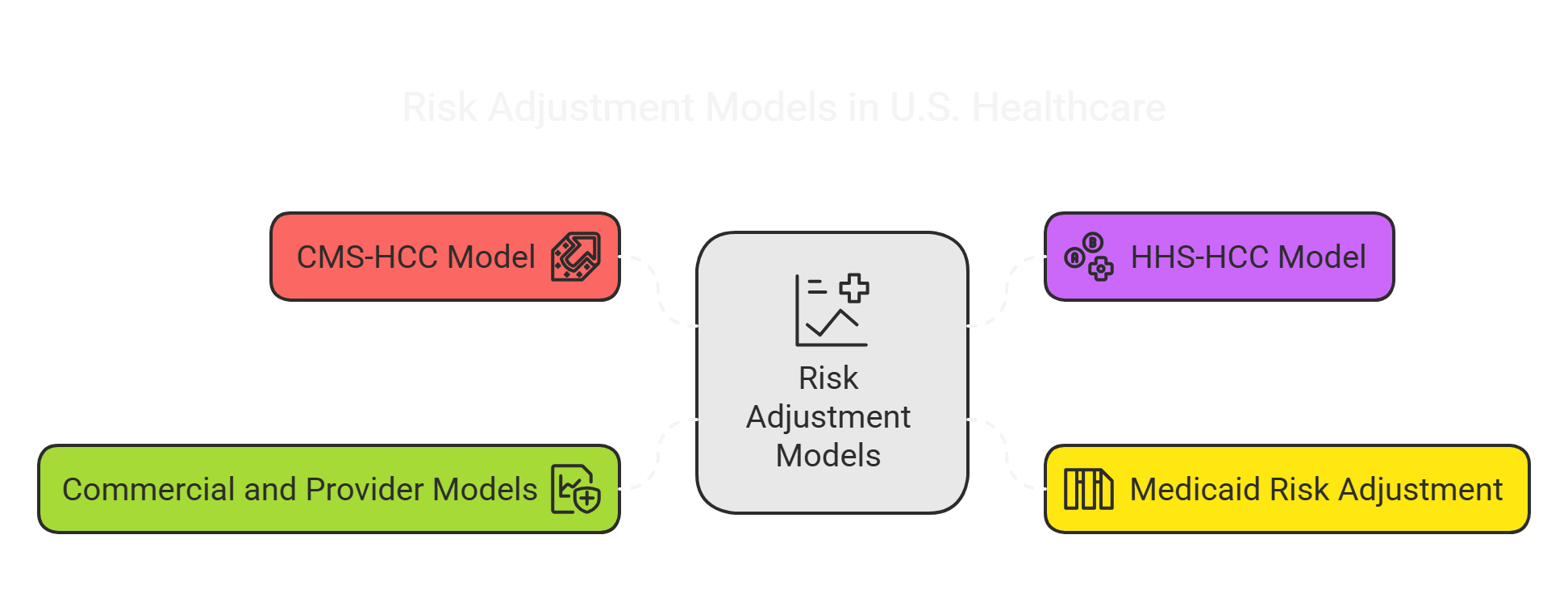

Beyond Medicare Advantage’s CMS-HCC model, other risk adjustment models include:

- HHS-HCC model: A similar methodology used for the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace individual and small-group plans. Administered by HHS, this model uses concurrent risk adjustment (using diagnoses from the same year) to transfer funds among insurers so that plans with sicker enrollees receive compensating payments.

- Medicaid risk adjustment: Many states Medicaid managed care programs use their own risk adjustment models (sometimes adapted from HCC or other models like CDPS) to adjust capitation payments for Medicaid beneficiaries.

- Commercial and Provider models: Health plans and provider groups may use proprietary models or tools like the Johns Hopkins ACG (Adjusted Clinical Groups) or Charlson Comorbidity Index for internal risk stratification and management. These aren’t used for CMS payments but help in predicting utilization and managing care for high-risk patients.

While the models may differ, the core principle is consistent: diagnoses and patient factors are converted into a risk score that adjusts payments or benchmarks. For executives, it’s important to know which model applies to your population. In Medicare Advantage, mastering the CMS-HCC model (including its periodic updates and nuances like disease hierarchies and interaction effects) is key to optimizing revenue. In ACA or Medicaid plans, understanding the local risk model is equally important. Ultimately, all these models serve to redistribute funds within a risk pool so that entities with sicker patients have more resources, aligning financial incentives with patient risk profiles.

Challenges in Risk Adjustment Accuracy

Achieving accurate risk adjustment is not without challenges. Several issues can affect the precision and fairness of risk scores:

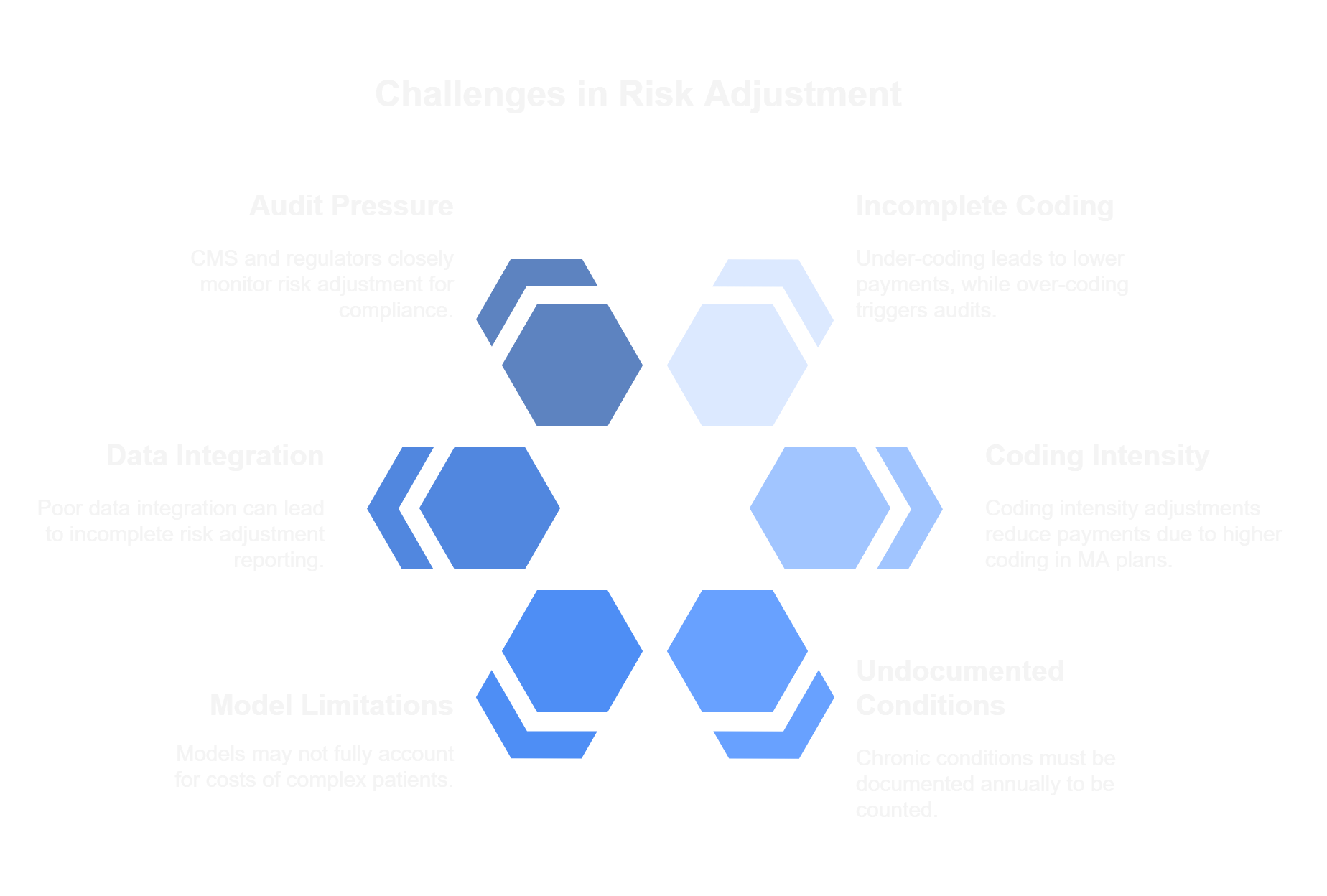

1. Incomplete or Inaccurate Coding:

Risk adjustment is only as good as the data submitted. If providers fail to document and code all of a patient’s diagnoses, the patient’s RAF score will underestimate their risk (leading to lower payments). This is common with chronic conditions that might be overlooked during healthy visits. All diagnosis codes must be backed by clinical documentation and come from a face-to-face encounter to count for risk adjustment. Conversely, if coding is done inaccurately or conditions are exaggerated (intentional upcoding), it inflates risk scores improperly and can trigger audits and penalties. Maintaining coding accuracy is a constant challenge – under-coding can hurt revenue, while over-coding is a compliance risk.

2. Coding Intensity and Variation:

Medicare Advantage plans have historically documented more diagnoses per patient than fee-for-service Medicare, a phenomenon known as coding intensity. As a result, CMS applies a coding intensity adjustment – essentially a across-the-board reduction in MA risk scores each year. Currently this adjustment is 5.9% per year, which amounted to about a $50 billion payment reduction over 2019-2021 to offset higher coding in MA plans. Plans face the challenge of improving documentation to capture true risk while knowing that industry-wide coding differences can lead to these mandatory payment cuts. Variation in coding practices between providers, regions, and plans also means risk scores might reflect coding effort as much as true health status, which is an ongoing concern.

3. Undocumented Conditions & Care Gaps:

Risk scores reset annually, so chronic conditions must be documented each year to be counted. If a member doesn’t have at least one visit where a chronic condition is noted, that condition “drops off” the risk profile for the next year. This can happen if patients skip annual check-ups or if providers focus only on acute issues. It’s a challenge to ensure that every relevant condition (especially those like diabetes, depression, or heart disease that persist year to year) is captured at least once annually. Health plans worry about “missed codes” – which represent needed services and costs that won’t be reflected in revenue.

4. Model Limitations:

No risk adjustment model perfectly predicts costs for every individual. Certain populations tend to be underpredicted. For example, prior analyses found that the CMS-HCC model historically didn’t fully account for the costs of patients with multiple serious chronic conditions – their combined illness burden led to higher spending than the model’s additive approach captured. Similarly, patients with functional impairments or high social risk factors (e.g., extreme poverty, homelessness) may incur higher costs not captured by standard HCC diagnoses. Most current models do not include social determinants of health in risk scoring.

This means plans serving socially at-risk populations might still find risk adjustment inadequate, a challenge as the industry looks to address health equity. (NCQA and other organizations have begun exploring adjustments or stratifications by socio-economic status to improve fairness in comparisons.) Keeping models up-to-date with medical advances and new diseases is also an ongoing challenge – for instance, as new expensive therapies emerge or as conditions like opioid use disorder rise in prevalence, the models must adapt.

5. Data Integration and Timeliness:

Risk adjustment relies on comprehensive data from across the healthcare continuum. If a health plan’s data integration is poor, diagnoses from specialists, hospitals, or post-acute providers might not make it into the risk adjustment reporting. Incomplete data capture leads to lower risk scores. Timeliness is another issue: there’s often a lag (MA risk scores use last year’s data for this year’s payments), so if a population’s health status worsens suddenly (say due to a pandemic), the payment model may only catch up the next year. Plans and providers must operate with this time lag in mind.

6. Audit and Compliance Pressure:

Due to the financial stakes, CMS and regulators closely monitor risk adjustment. Medicare Advantage plans are subject to Risk Adjustment Data Validation (RADV) audits where a sample of patient charts is reviewed to confirm that submitted diagnoses are supported by the medical record. If discrepancies are found, CMS can recoup payments for unsupported codes and, starting with recent rule changes, can extrapolate sample audit findings to the broader population – potentially leading to substantial claw-backs.

The Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Inspector General (OIG) has estimated that roughly 9.5% of payments to MA plans are improper, mainly due to unsupported diagnoses in risk adjustment submissions. This puts a spotlight on coding accuracy and documentation. Health plan executives must be vigilant; even unintentional errors can result in repayments, and intentional upcoding can lead to hefty fines under the False Claims Act. Staying compliant with CMS guidelines and audit requirements is an ever-present challenge as organizations strive to maximize legitimate risk scores without crossing regulatory lines.

In summary, ensuring risk adjustment accurately reflects patient risk requires constant diligence. It involves educating providers on documentation, deploying robust data systems, and monitoring coding patterns. The goal is a Goldilocks outcome: capture every valid diagnosis (no under-coding) but avoid coding anything that isn’t fully supported (no over-coding). Achieving that balance is difficult but critical for both financial performance and ethical, compliant operations.

Best Practices for Health Plans to Optimize Risk Adjustment

Health plans and provider organizations that excel in risk adjustment tend to follow a multifaceted strategy. Below are some best practices to support accurate and compliant risk adjustment:

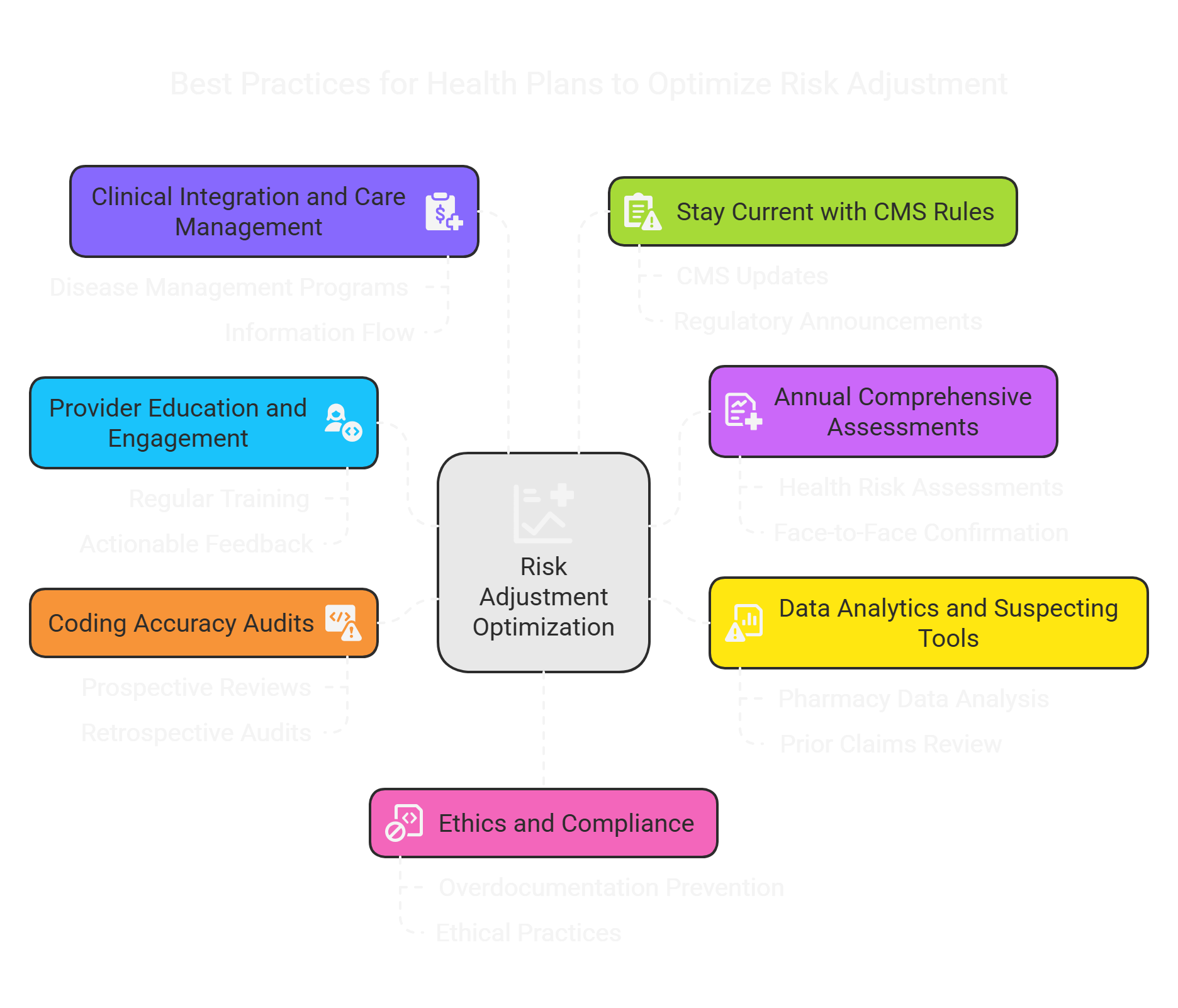

1. Provider Education and Engagement:

Invest in regular training for physicians, coders, and care teams about documentation and ICD-10 coding guidelines. Clinicians should understand that documenting all chronic and relevant acute conditions each year is vital. Encourage using precise language in medical records (e.g., linking complications to diabetes, stating conditions as “active” when appropriate). Engaged providers are more likely to document diagnoses properly. Providing actionable feedback – for instance, monthly reports on missing codes or suspected conditions – can keep providers attentive to coding accuracy.

2. Annual Comprehensive Assessments (Health Risk Assessments):

Conduct annual wellness visits or Health Risk Assessments (HRAs) to evaluate each member’s health status thoroughly. These assessments, often done in-home or in-clinic, help identify chronic conditions, behavioral health needs, and social factors. CMS considers HRAs a best practice for MA plans and in some cases requires them. The key is that any new diagnoses found in an HRA must be confirmed during a face-to-face encounter and documented in the medical record to count for risk adjustment. When done right, HRAs can close gaps in care and coding by catching conditions that might otherwise go unreported. They not only boost RAF scores appropriately but also connect high-risk patients to care management resources.

3. Data Analytics and Suspecting Tools:

Leverage analytics to identify “suspect” conditions – health conditions that a member likely has based on pharmacy data, prior claims, or demographic profiles but which haven’t been documented yet in the current year. For example, a patient on insulin likely has diabetes; if it hasn’t been coded this year, that’s a gap to address. Advanced risk adjustment software can scan patient data to flag these gaps. Analytics can also predict which members are likely to have undiagnosed comorbidities or which providers might be under-documenting. By using these tools, health plans can prioritize outreach (for instance, prompting a physician to evaluate a patient for a possible condition) and thus improve coding completeness.

4. Coding Accuracy Audits (Prospective and Retrospective):

Establish internal audit processes to review diagnosis coding both before submission (prospectively) and after (retrospectively). Prospective reviews might involve coders reviewing a provider’s documentation during the year (or even pre-visit charts) to ensure upcoming encounters capture all active conditions. Retrospective chart audits after claims are submitted can catch errors or omissions – for example, discovering that a documented condition wasn’t coded on a claim or that a coded condition lacked sufficient documentation. These audits should be non-punitive and educational. When errors are found, update the coding (if within submission timelines) and coach the provider on how to improve documentation. Consistent chart auditing and feedback loops can significantly improve coding accuracy over time.

5. Clinical Integration and Care Management:

Break down silos between the coding team and the care management/clinical team. Use risk adjustment data to inform care management – for instance, a high-risk score patient should be enrolled in disease management programs. Conversely, when care managers identify new problems (e.g., a patient mentions seeing a cardiologist for newly diagnosed heart failure), ensure that information flows to coding personnel so the diagnosis is captured. Treat risk adjustment as part of the care process, not just a finance exercise. This integration reinforces that the purpose of capturing diagnoses is to better understand patient needs and secure resources for their care, aligning clinical and financial priorities.

6. Stay Current with CMS Rules and Model Changes:

Make it someone’s job (or a team’s) to continuously monitor updates from CMS, OIG, and industry groups regarding risk adjustment. Models like CMS-HCC are updated – e.g., new version changes condition categories or weights – and coding guidelines evolve (such as how certain diagnoses must be documented). For example, CMS’s 2024 update removed some diagnoses like uncomplicated peripheral artery disease from counting toward risk scores. Health plans need to anticipate how such changes impact their revenue and strategy. Additionally, keep abreast of regulatory announcements about RADV audit protocols, coding intensity adjustments, or new compliance requirements. By staying proactive, executives can adjust documentation strategies and provider education before changes hit financials. Scenario modeling (what if certain HCCs drop in value next year?) can also help in planning.

7. Ethics and Compliance as Core Values:

Instill an organizational culture that prioritizes accurate coding for the right reasons – to reflect patient health status and needs. Make it clear that overdocumentation or upcoding is unacceptable, even if it could increase payments. Build compliance checks to catch any overly aggressive coding patterns. Remember that CMS’s audit net is tightening; it’s far better to forego a dubious code than to face repayments or reputational damage later. Emphasize to teams that the goal is proper documentation: “Document the care you provide, and code the documentation.” When leadership reinforces ethical practices, it reduces risk and builds trust with regulators and members. After all, risk adjustment is meant to support patient care, not game the system.

By implementing these best practices, health plans can improve their risk adjustment outcomes – meaning more accurate risk scores, optimized revenue to match patient needs, and strong compliance. Executives should view risk adjustment improvement as an ongoing quality initiative, akin to improving clinical quality metrics. It requires coordination across departments (clinical, IT, coding, compliance) and continuous refinement. The payoff is well worth it: better insights into your population, funding to support high-risk members, and avoidance of surprises in audits or financial results.

Regulatory and Compliance Considerations in Risk Adjustment

Risk adjustment in Medicare Advantage and other federal programs comes with a heavy regulatory framework. Leaders must navigate these rules to avoid pitfalls. Key considerations include:

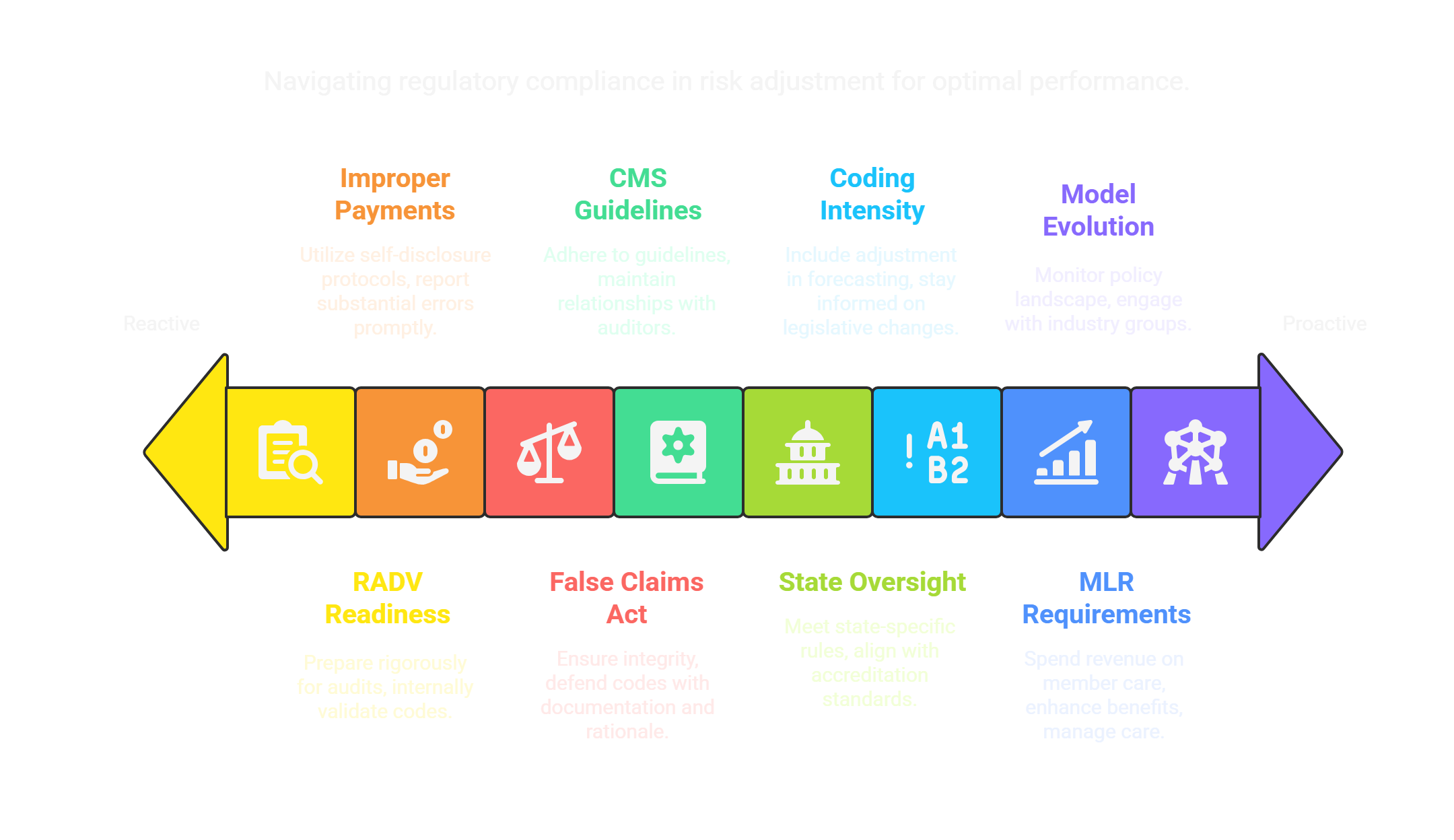

1. CMS Audits (RADV):

Medicare Advantage organizations are regularly subject to Risk Adjustment Data Validation audits. During a RADV audit, CMS reviews a sample of patient records to verify that each diagnosis submitted for payment is supported by the medical documentation. If a diagnosis code cannot be validated, the associated payment is deemed an overpayment. CMS recently finalized rules to extrapolate RADV findings, meaning if a certain percentage of codes in the sample are in error, that rate may be applied to the plan’s entire population – potentially recouping millions of dollars. Executives should ensure a state of audit readiness: rigorous internal validation of codes, well-organized medical records, and prompt response processes for any CMS requests. A proactive approach is to perform “RADV-like” mock audits internally to identify and correct issues before CMS finds them.

2. Improper Payment Risk:

According to HHS OIG, CMS estimates that about 9.5% of Medicare Advantage risk adjustment payments are improper largely due to unsupported diagnoses. That is a significant figure (several billions of dollars industry-wide) and underscores why compliance is closely watched. It’s crucial to understand that an unsupported code is effectively an overpayment that must be repaid. Plans should utilize the CMS Self-Disclosure protocol or other avenues if they identify substantial errors, as failing to report known issues could escalate into legal problems.

3. False Claims Act and Legal Scrutiny:

Submitting risk adjustment data comes under the federal False Claims Act if done fraudulently. The Department of Justice has pursued cases against some health plans and providers alleging intentional upcoding – for example, adding diagnoses that weren’t truly present or using chart reviews to capture codes without ensuring the condition was actively managed (the so-called “one and done” coding issue). The penalties in such cases can be steep (treble damages). While these are generally targeted at egregious behavior, it’s a reminder that integrity is paramount. All levels of the organization should be aware: only submit codes that you can defend with documentation and clinical rationale.

5. CMS Guidelines and Requirements:

CMS publishes detailed risk adjustment submission guidelines and model specifications. For instance, CMS requires that diagnoses come from acceptable provider types and settings – e.g., a physician or qualified practitioner in a face-to-face visit (telehealth is allowed in certain circumstances) – and be coded in accordance with official coding guidelines. Some encounters are excluded (like certain screening or lab results without a face-to-face visit). Staying within these rules is mandatory. Additionally, CMS updates the list of diagnosis codes that map to HCCs each year; if a code is reclassified or dropped, plans need to know. Having a strong relationship with your plan’s RADV auditor and CMS account manager can help keep current with expectation interpretations.

6. State and Accreditation Oversight:

Beyond CMS, state regulators (for Medicaid plans) and accreditation bodies like NCQA may have their own requirements. NCQA, for example, through its Health Plan accreditation and HEDIS measures, indirectly pushes plans toward robust data practices and may require certain risk stratification and quality improvement activities. Ensuring your risk adjustment practices also meet any state-specific rules (for Medicaid) or align with accreditation standards (like proper use of data for population health management) is important for a comprehensive compliance posture.

7. Coding Intensity Adjustment:

As noted, federal law mandates an adjustment to MA plan payments to account for differences in coding intensity. CMS sets this adjustment each year (the minimum is set by statute, currently 5.9%). While this isn’t something a plan can change, it’s a regulatory factor to include in forecasting. Essentially, even if a plan perfectly codes every condition, the revenue will be scaled down by this factor. Executives should be aware of this in bid projections and in explaining revenue to stakeholders. It’s also a topic of policy discussion – industry groups like AHIP often advocate around the fairness of this adjustment – so staying informed on any legislative changes here is wise.

8. Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) Requirements:

Medicare Advantage plans must comply with an 85% MLR, meaning 85% of revenue must be spent on medical claims or quality improvements. This is worth noting in risk adjustment context: any additional revenue gained from higher risk scores is largely destined to fund member care. In fact, MLR rules ensure at least 85% of MA revenue goes to patient care or quality programs. If a plan’s risk adjustment efforts bring in more money but they don’t spend enough of it on care, they’ll have to rebate the difference. This requirement reinforces that risk adjustment dollars should be used to benefit members (e.g., enhanced benefits, care management), aligning with the spirit of the program.

9. Future Model Evolution and Policy Changes:

CMS and other payers are continuously refining risk adjustment. There is growing interest in incorporating social risk factors or functional status into models to improve fairness. Pilot programs or new models (such as for specific Innovation Center demonstrations) may use modified risk adjustment approaches. Additionally, audits are becoming more sophisticated with data analytics, and oversight bodies (like OIG and GAO) regularly issue reports and recommendations on risk adjustment. Executives should keep an eye on the policy landscape – for example, proposals to change the coding intensity adjustment, or to adjust benchmarks in ACO models differently. Being engaged with industry groups (AHIP, Better Medicare Alliance, etc.) can provide a heads-up on changes coming down the pike.

In conclusion, compliance in risk adjustment is non-negotiable. A robust governance structure should oversee risk adjustment activities, including a compliance officer or committee specifically looking at audit results, coding outliers, and adherence to regulations. By fostering a culture of accuracy and transparency, health plans can avoid the common regulatory pitfalls and focus on the upside of risk adjustment: enabling better care through appropriate resource allocation.

Frequently Asked Questions about Risk Adjustment

Q: What is a Risk Adjustment Factor (RAF) score?

A: A RAF score is the numeric value that represents an individual patient’s expected cost risk relative to the average. In Medicare Advantage, the average beneficiary is assigned a risk score of 1.0 (roughly average cost). If a member has a RAF of 1.5, they are predicted to cost 50% more than average due to health conditions; a RAF of 0.8 would indicate 20% lower than average expected cost. The RAF score is calculated using a risk adjustment model (like CMS-HCC) based on the patient’s diagnoses and demographics. In short, the sicker the patient (more or severe diagnoses), the higher the RAF score.

Q: How often are risk adjustment scores updated for Medicare Advantage enrollees?

A: Risk adjustment scores in Medicare Advantage are updated annually. Each calendar year, CMS calculates a new RAF score for every enrollee using diagnoses from the prior year (typically from January 1 to December 31 of the previous year). These scores then apply to payments for the upcoming year. This means plans and providers must capture chronic condition diagnoses each and every year – if a condition isn’t documented in a given year, it won’t contribute to the payment for the next year.

CMS uses a prospective risk adjustment approach for MA (previous year data predicts current year costs). However, there are quarterly data submission cycles, so plans often get mid-year updates as more diagnosis data comes in, but the risk score model itself is recalibrated on an annual basis. The take-home point: risk scores reset each year, so comprehensive yearly documentation is critical.

Q: What are HCCs in the context of risk adjustment?

A: HCC stands for Hierarchical Condition Category. HCCs are groupings of related diagnoses that are used in risk adjustment models (especially the CMS-HCC model for Medicare). Each HCC represents a disease or condition (or set of similar conditions) and is assigned a risk weight. For example, HCC 18 might be “Diabetes with chronic complications” and carry a certain weight, whereas HCC 19 might be “Diabetes without complication” with a lower weight. The model uses these weights to calculate a person’s risk score.

The term “hierarchical” means the model only counts the most serious condition within a category hierarchy – so if a patient has diagnoses for both mild and severe forms of a disease, only the severe category HCC is used (to avoid stacking multiple related codes). HCCs simplify the thousands of ICD-10 codes into a manageable number of clinically similar categories for risk scoring. For executives, understanding HCCs is useful because improvement efforts often focus on specific HCC capture (e.g., better documentation of HCCs for major depression or heart failure). It’s the HCC categories, rather than individual ICD codes, that carry the weight in the risk formula.

Q: How does risk adjustment impact patient care?

A: Risk adjustment impacts patient care indirectly by influencing the resources and incentives available to care for patients. When risk adjustment works properly, a plan or provider serving a very sick population receives higher payments, which can be reinvested in care programs – such as care coordinators, disease management, home visits, or expanded benefits – for those high-risk patients. It also removes the financial disincentive to care for the sickest patients, thereby promoting access to care for high-risk groups. For example, before risk adjustment, plans might have avoided enrolling people with serious chronic illnesses; now, with risk-adjusted payments, those patients are not seen as financial liabilities but rather come with appropriate funding.

In value-based care arrangements, risk adjustment allows providers to focus on improving outcomes for all patients (regardless of complexity) because they know performance evaluations will account for patient acuity. Ultimately, patients benefit by getting more equitable care – plans and providers have the means to serve complex patients without jeopardizing their finances. That said, risk adjustment is mostly behind-the-scenes; patients usually won’t notice it day to day, but they do benefit when their doctors and health plans are empowered to address their full range of health issues.

Q: Is risk adjustment used outside of Medicare Advantage?

A: Yes. While Medicare Advantage was one of the early widespread uses of risk adjustment, the concept is used in many other healthcare programs. In the ACA Marketplace (Obamacare) individual and small group insurance markets, there is a risk adjustment program (run by HHS) that uses a similar HCC model to redistribute funds among insurers – plans with sicker enrollees receive payments funded by those with healthier enrollees. Many state Medicaid programs use risk adjustment to set capitation rates for Medicaid managed care organizations, accounting for differences in enrollee health status. Medicare Part D (prescription drug plans) uses a risk adjustment for drug spending (with RxHCC categories).

Additionally, in value-based payment programs like ACOs or bundled payments, risk adjustment is used to adjust financial benchmarks and quality metrics. Even employer-based insurance programs and provider groups use the principles of risk adjustment for internal budgeting or evaluating provider performance. In summary, any model where payment or comparisons need to be fair with respect to patient illness burden will incorporate risk adjustment. It’s a ubiquitous tool in moving healthcare away from one-size-fits-all payments to more nuanced, needs-based approaches.

Key Takeaways

- Risk adjustment ensures fair payment and evaluation by accounting for each patient’s health status. It “evens the playing field” so organizations caring for sicker patients receive adequate resources and are not penalized in performance comparisons.

- In Medicare Advantage, risk adjustment directly influences plan revenue through RAF scores. Plans are paid more for high-risk members and less for low-risk ones, which stabilizes finances and prevents cherry-picking of only healthy enrollees. Accurate coding of members’ diagnoses is therefore mission-critical for MA plan executives.

- Value-based care models (ACOs, capitated arrangements, etc.) rely on risk adjustment to set fair benchmarks and payment levels. This allows providers to focus on quality outcomes, knowing that higher patient acuity is accounted for in their targets. Risk adjustment supports population health management by aligning incentives with patient needs.

- CMS-HCC model is the standard for Medicare Advantage risk scoring. It assigns weights to condition categories (HCCs) based on diagnoses and demographics to produce a RAF score. Executives should be familiar with how this model works and its updates (e.g., CMS’s 2024 revision), as it directly affects revenue projections.

- Coding accuracy and documentation are the linchpins of successful risk adjustment. Under-coding (missing diagnoses) leads to underestimation of risk (and underpayment), while over-coding can lead to compliance violations. Regular provider training, chart audits, and data analytics are best practices to improve coding completeness and precision.

- Regulatory compliance is an ever-present concern. CMS conducts audits (RADV) to validate risk adjustment data, and regulators estimate a significant amount of improper payments stem from unsupported codes. Health plans must maintain rigorous compliance programs to avoid penalties. Ethical risk adjustment practices not only avoid legal trouble but build trust and ensure long-term sustainability.

- Continuous improvement is essential. Successful organizations treat risk adjustment as an ongoing process – keeping up with model changes, refining internal processes, and integrating risk adjustment with care management. The goal is to accurately reflect the illness burden of members, secure appropriate funding, and ultimately use those resources to improve care for high-risk individuals.